Introduction

In the span of just two days (2025 May 5 – 6), the Federal Reserve (Fed) purchased a staggering $34.8 billion in U.S. Treasuries through its System Open Market Account (SOMA). On May 5, 2025, the Fed absorbed $20.47 billion in 3-year notes; the next day, it added another $14.83 billion in 10-year notes. This marked the largest two-day Treasury purchase by the central bank since the quantitative easing (QE) era peaked in 20211.

While officials are unlikely to label these actions as QE, the scale and timing raise serious questions. Is the Fed quietly reintroducing liquidity support to the market? And if so, what does this signal about financial stability and the broader economic backdrop?

The Data: A Closer Look

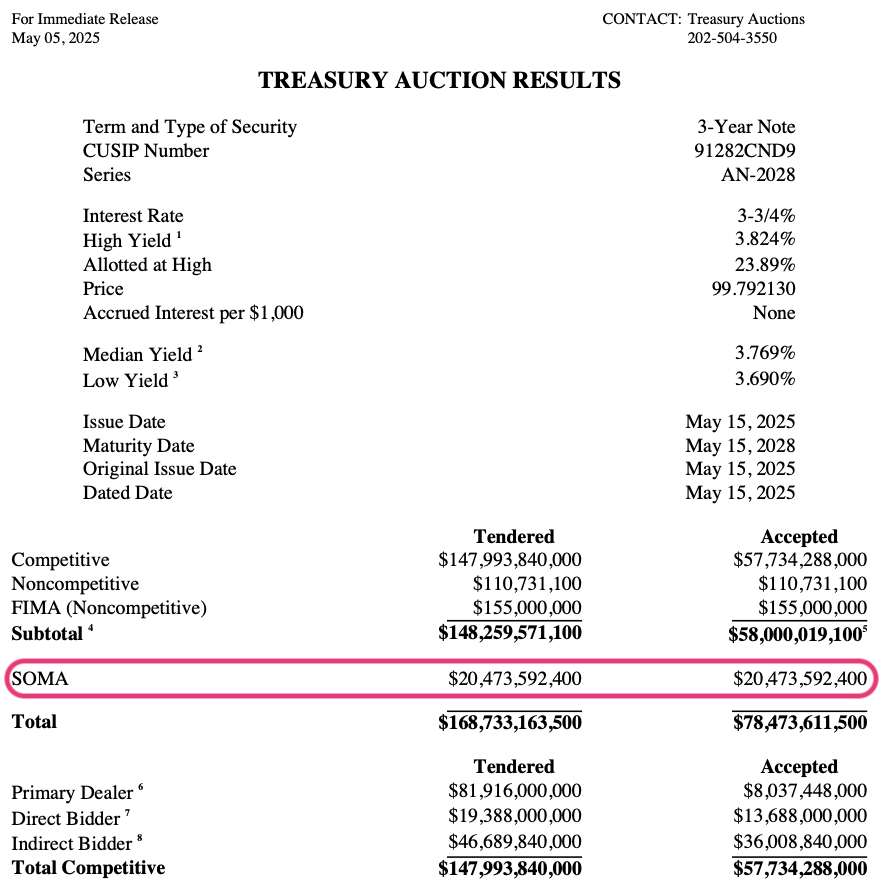

The May 5 auction results for 3-year notes (CUSIP 91282CND9) showed a total accepted amount of $78.47 billion. Of this, SOMA accounted for $20.47 billion, or roughly 26%. 2

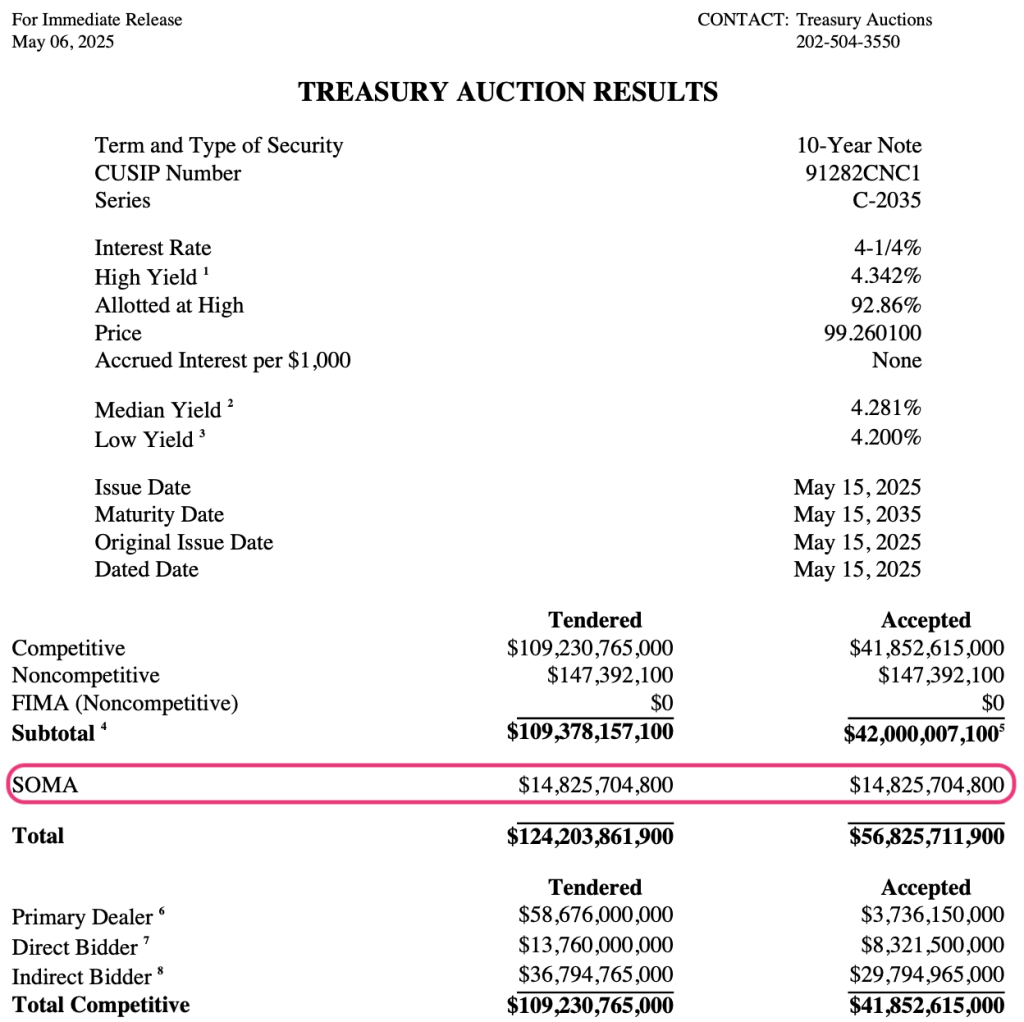

Similarly, the May 6 auction of 10-year notes (CUSIP 91282CNC1) saw total acceptances of $56.83 billion, with SOMA again taking approximately 26% of the total at $14.83 billion.3

In total, the Fed absorbed $34.8 billion across these two auctions, an amount that stands out starkly against the backdrop of stated policy normalization. The timing is even more intriguing given the $3.5 billion provided through the Fed’s Discount Window just a week earlier, hinting at underlying liquidity needs in the system.4

Why Now? Possible Interpretations

SOMA operations are standard tools for implementing monetary policy. Unlike formal QE programs, which are explicit policy shifts aimed at lowering long-term interest rates and stimulating economic activity, SOMA purchases are often routine or directed at rolling over maturing securities. However, the distinction becomes blurry when the Fed starts buying in size and in short order. So, why is the Fed buying so aggressively?

- Auction Support: The sheer volume of issuance in a rising deficit environment may have prompted the Fed to stabilize Treasury auctions by absorbing excess supply. Without this support, yields might have spiked uncomfortably higher.

- Liquidity Provision: The recent uptick in Discount Window usage suggests that some institutions may be experiencing short-term funding stress. SOMA purchases could be a way to add liquidity indirectly.

- Curve Management: With the yield curve showing signs of bull flattening and market expectations adjusting toward rate cuts later in the year, the Fed may be subtly guiding term premiums lower to support broader financial conditions.

- Global Demand Shortfall: If foreign or institutional demand for U.S. debt is weakening, the Fed might be stepping in to fill the gap and prevent disorderly market behavior.

Market Implications

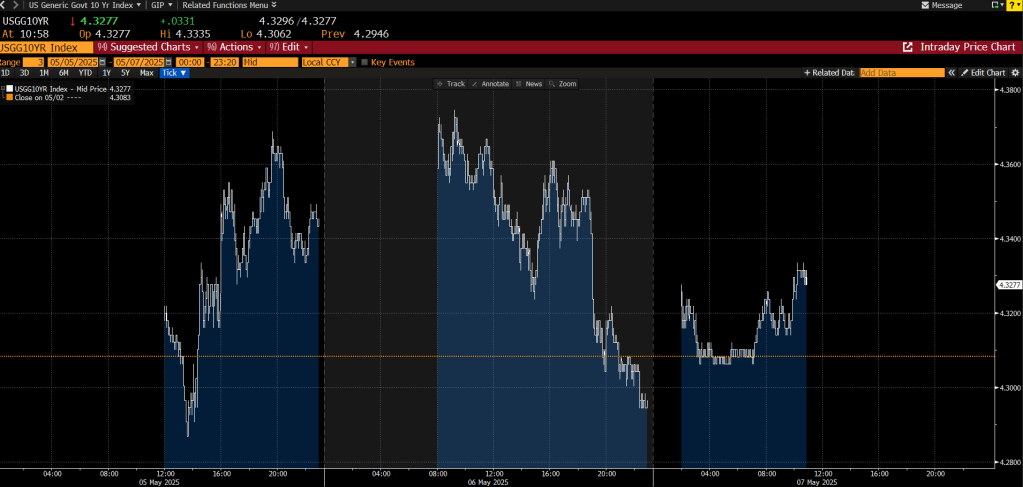

Whether or not this is officially QE, the market impact is real. Treasury yields dropped modestly following the announcements, particularly in the 10-year segment, where SOMA activity was concentrated. Risk assets also responded favorably, likely interpreting the purchases as a dovish tilt in policy.

US Government 10Yr 05/05 – 07/05 (source: Bloomberg Terminal)

This move may reignite the debate around moral hazard and the Fed’s role in perpetually underwriting markets. If investors begin to believe the Fed will intervene any time yields rise too quickly or liquidity dries up, it could distort risk pricing across asset classes.

Moreover, the scale of these purchases suggests that policy normalization may be running into structural limits. If the market cannot absorb Treasury issuance without significant Fed participation, that has long-term implications for debt sustainability and the independence of monetary policy.

Conclusion

The Federal Reserve’s $34.8 billion in Treasury purchases over just two days may not be labeled QE, but the market effects are strikingly similar. In a world where semantics often matter less than outcomes, investors should pay close attention to what the Fed does, not just what it says.

These actions hint at deeper fragilities in the financial system—perhaps in funding markets, perhaps in Treasury demand more broadly. Either way, the implication is clear: despite the official end of QE, the Fed remains an active and essential player in maintaining market stability.

Whether this is a one-off stabilization effort or the quiet beginning of a new liquidity regime remains to be seen. But for now, the message is unmistakable: QE may be dead in name, but not in practice.

Daniel Rivas

Leave a comment