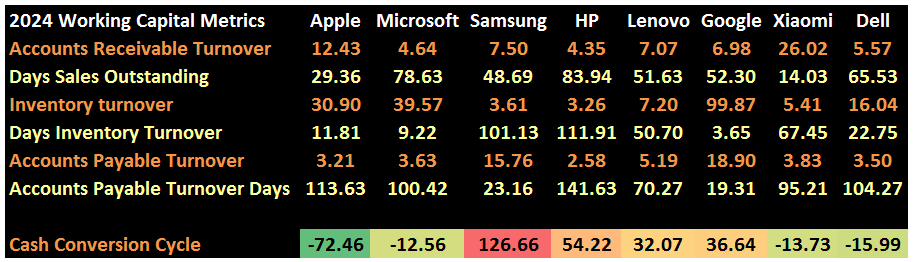

In the world of corporate finance, few operational metrics reveal more about a company’s internal efficiency and strategic power than the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC). While many investors and analysts focus on revenue growth or profit margins, the CCC quietly tells a deeper story: how fast a company can turn its investments in inventory and production into cash.

At the end of 2024, Apple reported a CCC of -72 days, meaning it collects cash from customers well before it pays suppliers or incurs full inventory costs. This working capital dynamic it’s a core enabler of Apple´s success. When compared to major tech competitors like Samsung (127 days), HP (54 days), Lenovo (42 days), and even operationally efficient giants like Google (40 days) or Microsoft (-12 days), the contrast becomes striking.

Even among the most advanced companies, none comes close to Apple’s CCC efficiency. While Microsoft, Dell, and Xiaomi also report negative CCCs, the magnitude of Apple’s lead, nearly 5x than its closest peers, translates to significantly more Working Capital flexibility.

Understanding the Cash Conversion Cycle

The Cash Conversion Cycle is a working capital metric that combines three components:

- DIO measures how long it takes to sell inventory.

- DSO measures how long it takes to collect payment from customers.

- DPO measures how long the company takes to pay its suppliers.

A negative CCC implies the company gets paid by customers before it pays suppliers, a structurally advantageous position that improves liquidity, reduces the need for external capital, and enhances return on invested capital (ROIC).

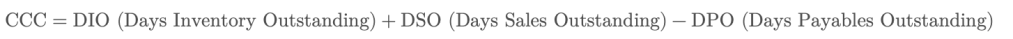

Apple’s Supply Chain

A detailed supply chain map from Bloomberg (as of May 2025) illustrates the structural mechanics behind Apple’s industry-leading negative cash conversion cycle.

On the supply side (left), Apple manages 696 suppliers, including major players such as Foxconn (Hon Hai), Luxshare, TSMC, Samsung, and Broadcom. These companies account for a substantial portion of Apple’s cost of goods sold (COGS), yet Apple exercises exceptional bargaining power over them. This is evident in its ability to stretch days payable outstanding (DPO) well beyond 100 days (113 days), effectively financing its operations using supplier credit. Notably, these suppliers are not commoditized vendors; they are often highly dependent on Apple for revenue, which reinforces Apple’s leverage in payment negotiations.

On the revenue side (right), the diagram highlights that 38% of Apple’s sales come directly from consumers, bypassing traditional intermediaries such as telecom carriers or wholesale resellers. This direct-to-consumer (DTC) model is a cornerstone of Apple’s working capital efficiency. It allows the company to collect immediate or prepaid cash from online and retail transactions, particularly during iPhone launch cycles (as later explained), dramatically compressing days sales outstanding (DSO) (i.e < 1 month). While other tech companies, such as HP, Lenovo, or even Samsung, rely more heavily on third-party retailers or enterprise distribution with delayed payment terms, Apple’s vertically integrated sales approach ensures faster cash inflow. Combined with delayed cash outflows to suppliers, this creates a powerful timing asymmetry: Apple receives cash early, pays late, and minimizes inventory holding through tight supply chain control.

To sum up, Apple’s CCC is consistently negative due to three operational characteristics: Advance cash collection from customers, efficient inventory management (Apple’s Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO) remains under 10 days, one of the lowest among global manufacturers) and dominant bargaining power with suppliers, reflected in its payments terms, with a DPO > 100 days.

Strategic Implications

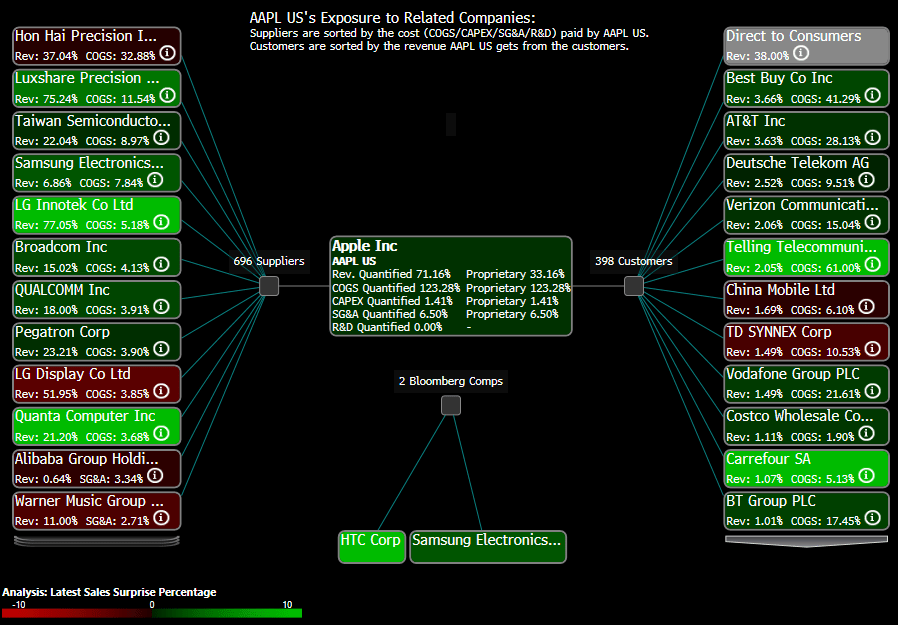

Apple’s negative CCC functions like an interest-free loan from customers and suppliers. This creates a self-reinforcing capital cycle; Apple can fund working capital internally, avoiding reliance on short-term debt, can invest in R&D, buybacks or CapEx projects and improves the Return On Invested Capital (ROIC), which in last instance shows how well the firm turns its investments into value.

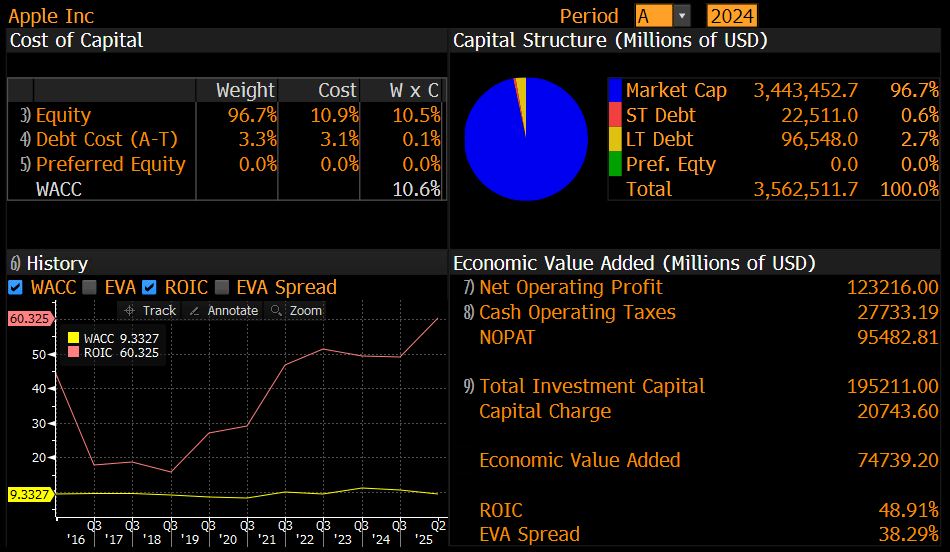

Apple’s ROIC in 2024 was 46.9%, meaning for every $1 it reinvested in the business, it earned nearly $0.47 in after-tax operating profit. But ROIC Analysis matters not just to assess how productively a company uses its capital, but to evaluate value creation: when ROIC exceeds the cost of capital (WACC), the company creates value = EVA.

By looking at the WACC analysis, in 2024 Apple created nearly $75 billion in real economic value above its required return, thanks largely to its ability to turn working capital quickly, a function of its deeply negative CCC.

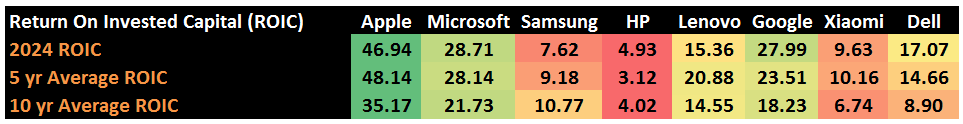

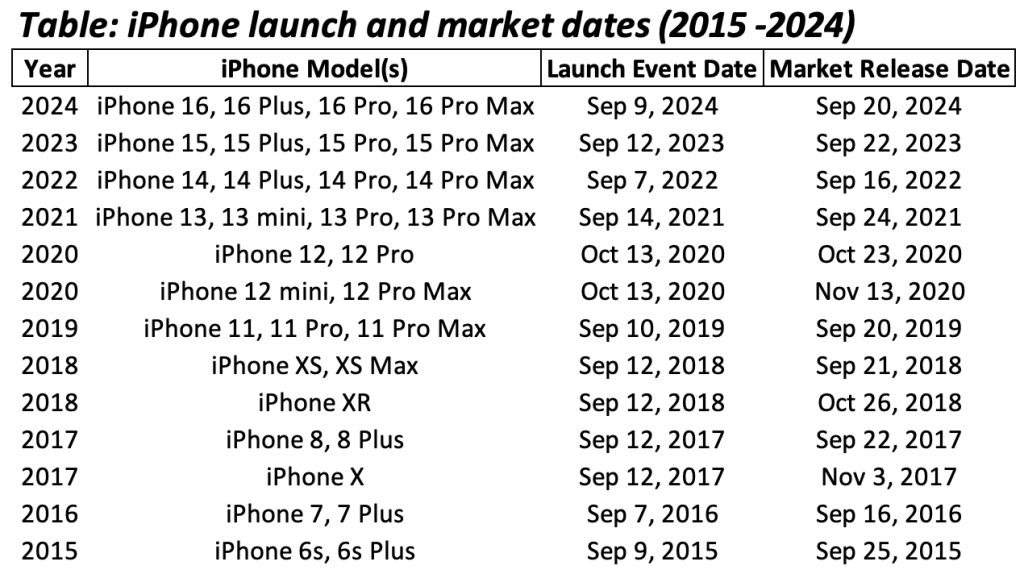

Case in Point: iPhone Launch Cycles

Apple’s CCC becomes even more powerful during major product cycles. For example, during iPhone releases:

- Customers pre-order and pay weeks in advance.

- Inventory turns over quickly due to high demand.

- Suppliers are often paid on 60- to 90-day terms after the device ships.

The chart above shows Apple’s Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) in orange over the past decade, overlaid with the company’s stock price in white. Each sharp drop in the CCC corresponds to a major iPhone launch cycle, from the 6s to the 16, when Apple collects billions in preorders and upfront payments before incurring full inventory or supplier costs. These recurring negative CCC spikes reflect Apple’s repeatable timing advantage, where customer cash flows in before supplier cash flows out, fueling liquidity and reinvestment just as competitors face capital drag.

Why This Is Not the Same for Others:

- Samsung:Offers preorders, but usually with delayed or partial payment, often via telecom carriers who settle after delivery. Carrier-led models slow down cash collection.

- Xiaomi: Competes on low margin and price; preorders exist but not at Apple’s scale, and many involve distributors, who delay cash flow.

- HP, Lenovo, Dell: Preorders are limited and mostly in B2B/enterprise, where payment terms are often Net-30 or longer. No upfront consumer cash collection.

- Google: Preorders for Pixel or Nest devices exist, but volumes are relatively small, and payment often occurs upon shipping.

- Microsoft: Preorders exist for Xbox or Surface, but like Google, not core to revenue, and not collected weeks in advance at scale.

Conclusion: CCC as Competitive Weapon

Apple’s negative cash conversion cycle is far more than an operational oddity, it is a strategic engine of capital efficiency and long-term value creation. Unlike competitors who must wait to collect cash and carry substantial working capital, Apple’s model, built on direct-to-consumer cash collection, lean inventory management, and delayed supplier payments, flips the traditional working capital model on its head.

Daniel Rivas

Leave a comment