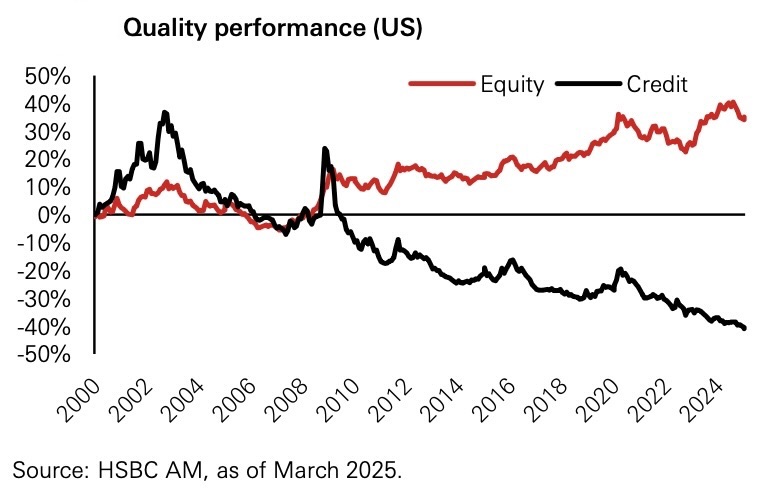

In the world of factor investing, the quality factor has earned its reputation as one of the most consistent sources of long-term outperformance in equity markets. High-quality companies, those with robust profitability, strong balance sheets, and stable earnings, have systematically delivered higher risk-adjusted returns than their lower-quality peers. Yet this seemingly universal principle doesn’t hold when we cross over to the credit markets. In corporate bonds, investors do not see a comparable quality premium, since quality tend to deliver lower (not higher) returns, aligning with their lower default risk and more conservative profiles.

HSBC Asset Management. (2025, April)1

This contrast raises a fundamental question: why is quality rewarded in equities but not in credit? And what does this mean for investors designing factor-based strategies across asset classes?

Introduction: Defining “Quality” in Equity and Credit Markets

Quality as an investment factor lacks a universal, rigid definition, but broadly it refers to companies with superior fundamentals.

In equity markets, those fundamentals refer to profitability, stabilty and management, which can be desaggregated into “hard” metrics (e.g, high ROE, strong profit margins, low debt leverage, consistent earnings growth and high FCF) and “soft” metrics (e.g, competitive advantages, brand strength and strategic positioning).

In credit markets, “quality” denotes issuers with stronger financial health (i.e higher credit ratings, lower leverage…)

Quality in Equities: A Proven Source of Alpha

The academic and empirical evidence supporting quality in equities is deep and global. Studies by Fama and French (2015)2 and Novy-Marx (2013)3 consistently show that high-quality stocks, those with strong operating profitability, stable earnings, and conservative investment, have outperformed “junk” stocks over decades and across regions.

Importantly, the quality factor is not just a high-return strategy, it’s also defensive. Quality stocks tend to hold up better during bear markets and recessions. For example, Baker and Wurgler (2006)4 found that during market downturns, high-quality stocks outperformed low-quality counterparts by as much as 5% annually.

There’s also a behavioral element: investors often chase high-beta, speculative stocks, overpaying for the dream of outsized gains and ignoring the compounding power of profitable, stable firms. This creates systematic mispricing, which patient investors can exploit by tilting toward quality.

Quality in Credit: Safety Without Outperformance

Contrast this with the credit markets, where buying higher-quality bonds (e.g., those from more profitable, conservatively managed issuers) does not lead to outperformance. In fact, the opposite is often true: quality bonds deliver lower yields and lower returns, precisely because they’re safer. Investors are compensated in credit for taking default and liquidity risk, not necessarily for picking the best-run companies.

Empirical studies confirm this. Within IG bonds, quality metrics like ROE or earnings stability have shown little to no correlation with excess returns. A quality tilt in credit typically reduces volatility, but at the expense of yield, with little evidence of alpha. Only in high-yield markets, where mispricing and default risk are more pronounced, has avoiding the lowest-quality issuers sometimes added value. But even there, the payoff is episodic, not persistent.

Why the Difference? Structural and Behavioral Drivers

There are both structural and behavioral reasons for this divergence between equities and credit.

First, equity markets are more prone to mispricing. Investors may chase stories and hype, overlook fundamentals, and exhibit biases toward volatility and risk. High-quality stocks can become undervalued as investors flock to glamorous but unprofitable firms, particularly during bull markets. The eventual reversion of sentiment creates opportunities for quality-focused strategies.

In contrast, credit markets are dominated by institutional investors (i.e pension funds, insurers, and banks) who are highly sensitive to credit risk and governed by regulatory capital rules. These investors often prefer higher-rated issuers and demand reliable interest payments, not capital gains. As a result, quality is already priced in through tighter credit spreads, leaving little room for alpha.

Second, the payoff structure differs. Equities have unlimited upside, allowing quality stocks to be re-rated dramatically if sentiment improves. Bonds, by contrast, have capped upside, typically par, so even if an issuer’s quality improves, the bond’s price can’t rise significantly. This limits the ability of credit investors to capture mispricing via fundamentals.

Finally, implementation matters. In equities, long–short quality-minus-junk strategies are straightforward and widely used. In credit, shorting individual bonds is expensive and illiquid, making it hard to run a true long–short quality strategy. Without that arbitrage mechanism, systematic mispricing is harder to exploit.

Implications for Factor Investing

For equity investors, the takeaway is clear: quality works. Whether through smart beta ETFs, fundamental tilts, or long–short factor portfolios, quality enhances performance, reduces drawdowns, and complements cyclical factors like value and momentum.

In credit, however, quality should be seen as a risk-control tool, not a performance enhancer. Bond investors seeking excess returns should focus on factors like value (carry), momentum, and low-risk. These have shown stronger and more consistent results across credit markets. Quality may still have a role, helping avoid downgrades, defaults, or “value traps”, but not as a standalone alpha source.

There is one notable crossover application: using equity quality as a hedge for credit portfolios. Since equity quality tends to outperform during credit stress (when spreads widen), it can serve as a positive-carry hedge, unlike shorting junk bonds or buying CDS, which are costly. This insight allows multi-asset managers to design more efficient and diversified strategies.

Conclusion

The quality premium is not a universal law, it is a market-specific phenomenon. In equities, quality reflects both investor behavior and structural inefficiencies, offering a rare combination of upside and downside protection. In credit, by contrast, quality aligns closely with lower risk, and lower return.

For investors, understanding these dynamics is crucial. Quality pays in stocks. It protects in bonds. Allocate accordingly.

Daniel Rivas

- https://www.assetmanagement.hsbc.co.uk/en/institutional-investor/news-and-insights/investment-outlook-q2-2025 ↩︎

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304405X14002323 ↩︎

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304405X13000044 ↩︎

- https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~jwurgler/papers/wurgler_baker_cross_section.pdf ↩︎

Leave a comment